Literary route through Gongora's Cordoba

Luis de Góngora y Argote (Cordoba, 1561-1627) was a priest, poet and playwright of the Golden Age, a leading exponent of the literary movement known as "Culteranism" or "Gongorism", later to be copied by other artists.

Maestro from the Golden Age

Luis de Góngora y Argote was the son of the judge of the Holy Office of Cordoba Don Francisco de Argote and Lady Leonor de Góngora. His comfortable financial situation allowed him to be well educated which led him to studying in Granada and Salamanca, where he was ordained as a priest in 1585 and was appointed canon at Cordoba Cathedral. He held the post of distributor of rations at the cathedral and, it appears, not with the austerity expected from someone of his rank.

From 1589 he travelled in various commissions of the council of canons in Navarre, in Andalusia and both Castilian Regions (Madrid, Salamanca, Granada, Jaén, Cuenca, Toledo). At this time he composed numerous sonnets, romances and satirical and lyrical ballads.

En 1609 he returned to Cordoba and began to intensify the aesthetic tension and the Baroque style of his verses. Between 1610 and 1611 he wrote the Oda a la toma de Larache and in 1613 Polifemo, a poem that paraphrases a mythological passage from the Metamorphoses by Ovid. That same year he presented his most ambitious poem at Court, the incomplete Soledades.

He gained even greater prestige, to the point that Philip III appointed him royal chaplain 1617; to perform this office he lived at Court until 1626.

The following year, 1627, he lost his memory and left for Cordoba, where he died of an apoplexy in extreme poverty. Velázquez portrayed him with a wide, open forehead, and from lawsuits, documents and the satires by his great enemy, Francisco de Quevedo, we know that he was jovial, sociable, talkative and a great lover of luxury and entertainmentlike card games and bullfighting, so much so that he was often reproached for wearing his priestly robes with little dignity.

Literary route through Gongora's Cordoba

En 1585, during a trip to Granada which lasted longer than expected, friends of Luis de Góngora in Cordoba wrote him a letter. In it they are asked him if he had forgotten the city where he had been born. Questioned about affection and nostalgia, the poet wrote a sonnet – “Oh excellent wall, oh crowned towers/of honour, of majesty, of nobleness…” - which today can still be read at one of the stops along the literary route around a citywhose illustrious writers included the author of Las Soledades and the poet Ricardo Molina.

The Calahorra Tower is the first stop on this route. The Roman Bridge one which stands at its feet represents the gateway to ancient Cordoba. With his heart divided between Cordoba and Granada, Góngora brought it to life in his verses when talking about “the noble sands” of the Guadalquivir River but "not golden" like those of the Darro River which washed Granada. After crossing the Roman Bridge and the Paseo de Isasa, you come to the Paseo de Ribera where there is a small monument in honour of Góngora and the sonnet with which we began this chronicle.

The poets of the Generation of '27 admired the work of this 17th century poet. That is why there are links between the book of poems called Canciones by Federico García Lorca and the sonnet by Góngora: both took the same route, from Granada to Cordoba, and are located at the entrance to the city. Retracing your steps to the Triumphal Arch of San Rafael, the route invites you to read the poem about the saint which Lorca included in Gypsy Ballads. From the Arch you can make out two Cordobas, separated by the Roman Bridge: the Roman-Christian and the Moorish-Muslim. The city pays great devotion to San Rafael, represented by the Triumphal Arch and acknowledged by Lorca in his poem.

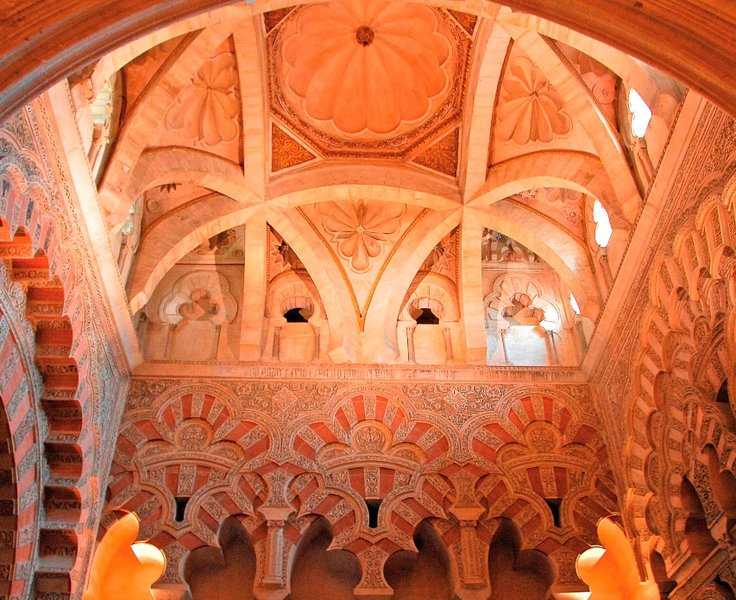

The old Mosque, the third stop on the literary walk, houses the Patio of the Oranges, at the foot of the cathedral tower, which Ricardo Molina referred to as the “island of shade, silence and perfume.” The Mosque, in the words of Antonio Gala, “was the heart of Cordoba when Cordoba was the heart of the world”, and which in its patio, this patio, “the Fuquha administered justice and the teachers provided wisdom; the wealthy bid for ancient monuments and rare works of art at auctions; young lovers recited love poems; scholars sat cross-legged reading the wisdom of the learned; slaves played and sang songs from their homelands, and girls danced with their breasts held high...” Around the fountain of Santa María, water flows from four spouts, together with popular beliefs, the best-known them being the spout of the Olive Tree, to which love powers are attributed.

The route continues on to the Plaza del Potro, where you'll find one of poems from the book Elegías de Sandua (1948) by Ricardo Molina. In the Cordoba of the Golden Age, all roads led to El Potro, so it is not surprising that literary route passes this way, just like the poet during his meditative walks. For several centuries El Potro was the centre of commercial life and communications between Cordoba and the rest of Spain. Miguel de Cervantes mentions this square in Don Quixote and in Rinconete y Cortadillo. The natives of this neighbourhood were reputed to be brave, smart, amusing and alert, hence the popular saying “try the other one, 'cos I'm from El Potro."

Near to this stop, in the Calle Lineros nº 26, is where the poet Ricardo Molina lived, as commemorated by a simple plaque which says "this is the house where the illustrious poet, Ricardo Molina, created his most important literary and Flamenco work." There is also a place for the gardens of the Christian Monarchs' Fortress in this literary walk. This is the place which inspired Molina when he wrote the poem Letter to Vicente Aleixandre, which is included in his book A la luz de cada día.

Continuing towards the Jewish Quarter, the last stop on the route, you'll come to the Calle Tomás Conde, near the Caliphal Baths, where in one of the houses the poet Luis de Góngora was born. The house where he was born was the venue for frequent meetings with his friends and where he had a large library. Further to the north is the Plaza de la Trinidad where stands a statue-tribute to the poet, since it was in one of these houses where he died, specifically in the one on the corner with the Calle de las Campanas.